Memory in Rust

Introduction I recently started getting more and more into Rust, as I wanted to adopt a...

Introduction

I recently started getting more and more into Rust, as I wanted to adopt a fast programming language into my tech-stack. Coming from Java and Ruby I had various mountains to climb, one of them being Rust and its relation with memory. This article aims to explain it in an way that is easy to grasp for beginners.

Memory allocation

To understand ownership and borrowing we first need to understand how the memory is allocated. Rust allocates memory based on if the data size is fixed or dynamic.

Static Allocation

On data types like i32 that have a fixed memory size, rust opts for static allocation on the stack.

Dynamic allocation

Dynamic memory allocation happens on the heap. In this case, the needed memory to store a value can change over time, like with the String type:

let mut string = String::from("abcd");

s.push_str("efgh");

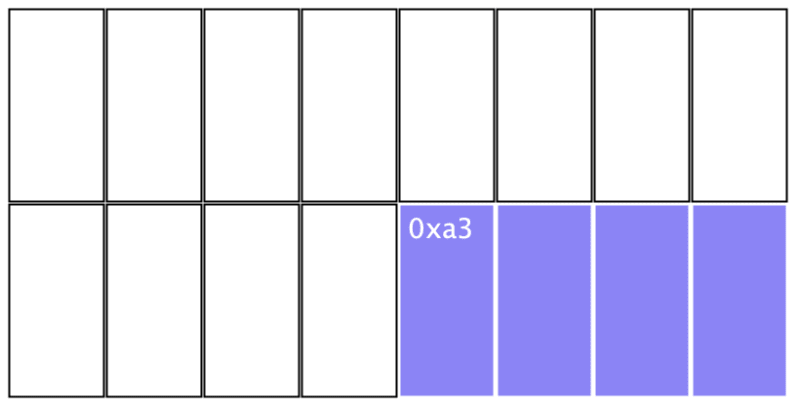

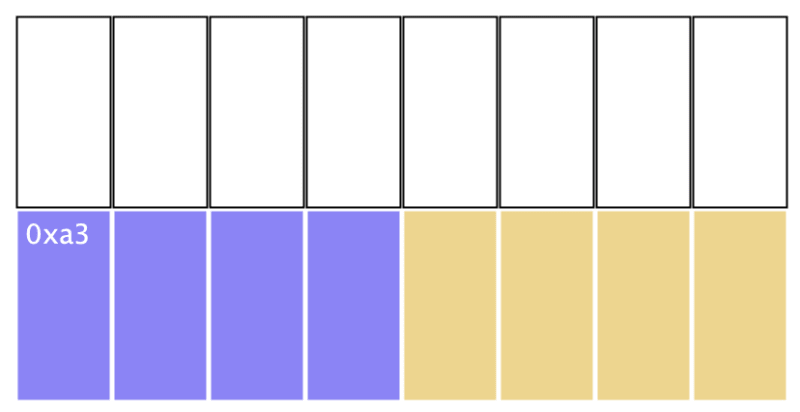

In this case (assuming the String is UTF-8 encoded) the variable first needs 36 bits and then 72:

Memory management

Rust manages the memory at compile time, which means it doesn't have a garbage collector to find dead memory. That allows the code to run faster, but can also be the cause for memory leaks. To circumvent leaking memory and causing the code to slow down or crash after a while, the developer has to follow a strict set of rules. Those can primarily be split up into:ownershipandborrowing.

Ownership

Every value in Rust has a variable that owns it. So for example:

let x = 5;

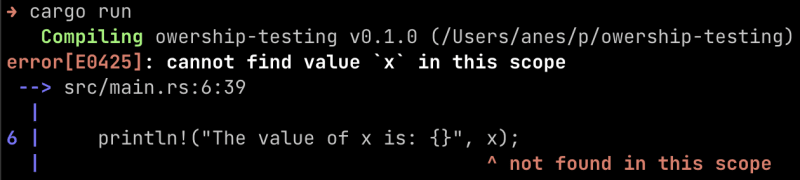

Would make x the owner of our 5 . When x goes out of scope the value will be dropped, as there isn't any owner left. That would look as follows:

{

let x = 5;

println!("{}", x); // This prints: "5"

} // Here the memory is dropped

println!("{}", x); // This gives a compiler error

And when we check what the compiler says we see exactly what we predicted:

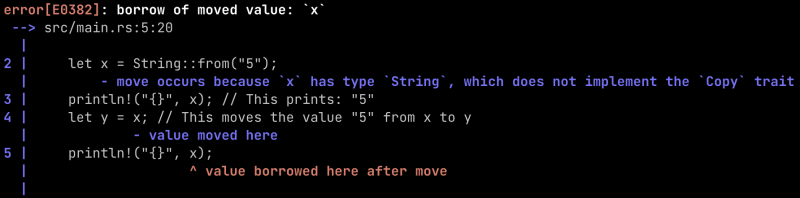

Now when we assign x to another variable, like y normally we change the owner. That means, that after we do let y = x accessing the variable x will render an error. Following code example is used:

let x = String::from("5"); // Initialize x as "5"

println!("{}", x); // This prints: "5"

let y = x; // This moves the value "5" from x to y

println!("{}", x); // This throws an error

Here, the second println! statement will error, as we try to borrow (explanation in next chapter) x , after it has been moved to y :

It's quite visible what happened: x does not hold the value anymore.

If you're wondering why rust doesn't allow two variables to reference the same value, consider this scenario:

{

let x = String::from("5")

let y = x

} // On line four the value references by x and y goes out of scope, which makes rust call the drop function (in the case of dynamically allocated values) to free the memory. Now because both variables go out of scope it runs drop(x) and drop(y) , which causes a "double free condition", which means that both try to free the same memory. This won't happen with languages that have a garbage collector, because the collector properly clears.

The copy trait

While that's the default behavior, certain types like integers, floats, etc. implement the Copy trait, which changes how the move operation behaves.

Let's take the move code again, but with i32 as its data type instead of String :

let x = 5; // Initialize x as an i32

println!("{}", x); // This prints: 5

let y = x; // This copies the value instead of moving it

println!("{}", x); // Now this works fine

When can we copy and when not?

If we think back on how memory is allocated, it should be pretty obvious: If a variable is statically allocated the Copy trait is included.

The issue with having the String type implement Copy is, that copying a String can potentially be very expensive as its size differs.

Borrowing

The issue with rusts ownership system is, that with a few function calls we can quickly have a lot of variables. That can look as follows:

fn main() {

let s1 = String::from("hello");

let (s2, len) = calculate_length(s1);

}

fn calculate_length(s: String) -> (String, usize) {

let length = s.len();

(s, length)

}

A better approach would be to using "borrowing". A borrow is signalized with the & symbol. That gives the variable temporary ownership over the variable.

A simple example would be this:

let mut x = String::from("Hello");

let y = &mut x;

y.push_str(", world");

x.push_str("!");

println!("{}", x);

Here we are able to push to x by accessing both x and y . The difference to just doing let y = x is, that the type of y is different now:

fn main() {

let mut x = String::from("Hello");

let y = &x;

print_type_of(&y); \\ &alloc::string::String

let z = x;

print_type_of(&z); \\ alloc::string::String

}

fn print_type_of(_: &T) {

println!("{}", std::any::type_name::())

}

We can also improve our function from before by using borrowing:

fn main() {

let s1 = String::from("hello");

let len = calculate_length(&s1);

println!("The length of '{}' is {}.", s1, len);

}

fn calculate_length(s: &String) -> usize {

s.len()

}

Already looks much cleaner, doesn't it.

De-referencing

Let's say we want to create a function that takes in a i32 x and mutates that value. The first thing that comes to mind would be as follows:

fn main() {

let mut x: i32 = 10;

double_number(&mut x);

println!("the value doubled is {}", x);

}

fn double_number(x: &mut i32) -> () {

x *= 2;

}

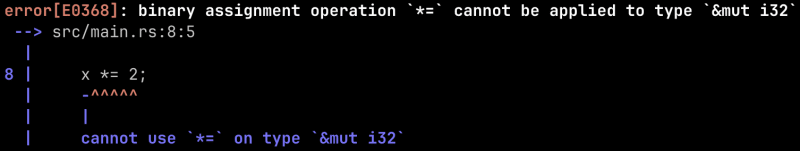

But this will throw an exception, as x (inside the function scope) is only a reference to the value, instead of the value itself:

It is only the reference, because the parameter x has been borrowed by using & when passing it. Now if we want to access and manipulate the value we "de-reference" it by using a * . Here is the same function, but corrected:

fn main() {

let mut x: i32 = 10;

// double_number(&mut x);

println!("the value doubled is {}", x);

}

fn double_number(x: &mut i32) -> () {

// x *= 2; // This would mutate the pointer position x

*x *= 2; // This will mutate the value at the pointer position x

}

An example that is easier to understand:

let mut x: i32 = 10;

let y: &mut i32 = &mut x;

*y += 1;

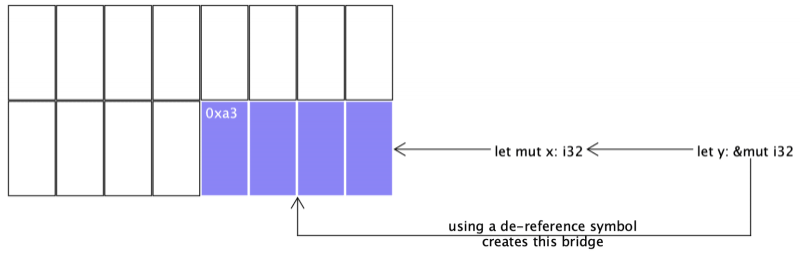

Here we are making y a mutable borrow of x , i.e. a reference to x . To then be able to manipulate the value x trough y , we "de-reference" it.

We can visualize it like this:

Conclusion

Rust trades off efficiency for simplicity, which can make it hard for developers to understand how memory is managed. I hope you were able to learn something from this article.